Life in a universal space

Vicky Richardson returns to Royal Leamington Spa to report on life in our new home.

Words: Vicky Richardson

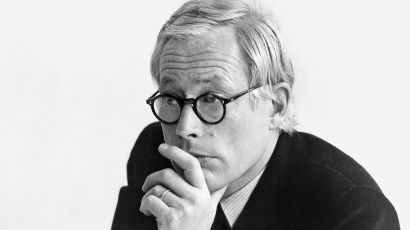

Photography: Dirk Lindner

The popularity of Victorian warehouses and 1930s factories as spaces to work and live in seems to prove that successful buildings are those that can adapt and change. Yet during the construction of Vitsœ’s new building, Mark Adams (managing director of Vitsœ) found himself resisting requests from consultants to design the interior for specific functions. His hunch was that the building should give the Vitsœ team the freedom to self-organize, and to create chance encounters between people, leading to better decision-making and a more satisfying work environment.

Just a few months after moving in it’s clear that Adams was right to insist on keeping the space open and free from partitions, and it’s fascinating to see how a new way of working is emerging at Vitsœ. This is coming about not by means of the building programming or enforcing a particular way of behaving or interacting, but by allowing staff to initiate their own work practices.

The first noticeable change is the nature of meetings, which in most workplaces are formal and limiting. Instead, conversations now take place ‘on the hoof’, and sometimes in the more relaxed setting of the kitchen – one of the few spaces designed for a specific function. It came as a surprise to most at Vitsœ that the kitchen has become so important. New anchor points for the day are breakfast, morning coffee and lunch, when everyone gets together as a company to eat and have conversation. A pattern to the day is evolving around the kitchen, with Vitsœ’s chef Will Leigh, former executive chef at the Royal Shakespeare Company, in a key position.

“The meal table brings people together,” said Adams. “At lunch I’ve counted five separate conversations going on between groups, with not a single phone in use. Some might be about what was on TV last night, but others are about work ideas.”

Lily Worledge, team leader for cabinet assembly who has worked at Vitsœ for nearly five years, commented, “previously you could go for a whole day or week without seeing people from the office. Now everyone goes through the same entrance and shares the same space.”

Suppliers, who are a key part of Vitsœ’s operation, are also part of the conversation. Bringing everything from extrusions, wood panels, screws, drills, cardboard boxes and packing tape, they often arrive for morning coffee and stay for lunch. Since moving in, Vitsœ’s relationship with them has been transformed.

Vitsœ’s employees have experienced the biggest change, relocating from the constrained environment of the previous factory in Camden Town, London. Seeing the building in use is, in fact, a great reminder of the power of solving problems collectively. Social, rather than architectural, structures have become the organizing principle of a typical day at Vitsœ.

Daniel Calderbank has worked with Vitsœ for five years, overseeing design and fabrication processes. For him, the new building gives more space and options for flexibility: “The old building dictated how we did things. It wasn’t a choice, it was the only way. Being here has opened up different options and means we can plan together as a team.”

Lily Worledge finds that the layout of the production space where cabinets, chairs and shelving systems are assembled is still evolving: “What’s nice is that we can adapt to the demands of the making process without the constraints of a small space. Before we moved in I drew up a rough plan of the area which was similar to the previous layout. But it has changed five times since then and it’s still changing.”

Ultimately, the nature of people’s roles is also changing as they take control of their environment and the way they work. It seems that the building is generating a new sense of self-confidence. Things that could be a problem now seem manageable.

Acoustic separation is probably the biggest challenge of working in a large, unprogrammed space. But the team are tackling this by talking it through, and are planning some experiments over the coming months to figure out solutions. One idea is to replicate, on a larger scale, the acoustic hoods you would find on old telephone boxes, which created pockets of quiet in a busy railway station.

Perhaps the most tangible improvement for Vitsœ’s team is the obvious one – moving from a relatively dark, constrained urban environment to a light airy space. According to Worledge: “the previous workshop was over-crowded, badly lit and had no views. Now we can see in four directions. It feels so much better. I feel healthier, just being able to look out and open the windows.”