A Lego mindset

How Dylan Smith’s love of Lego led to working at Vitsœ

Words: Vitsœ

Photography: Kasia Bobula

“Did you grow-up playing with Lego?” A question often asked at interview of someone applying for a role at Vitsœ. It seems a logical question to those of us who work with a certain shelving system on a daily basis, as not only we, but frequently others, describe 606 as ‘Lego for grown-ups’. However, Lego is not only for children, for some it can become a lifetime passion.

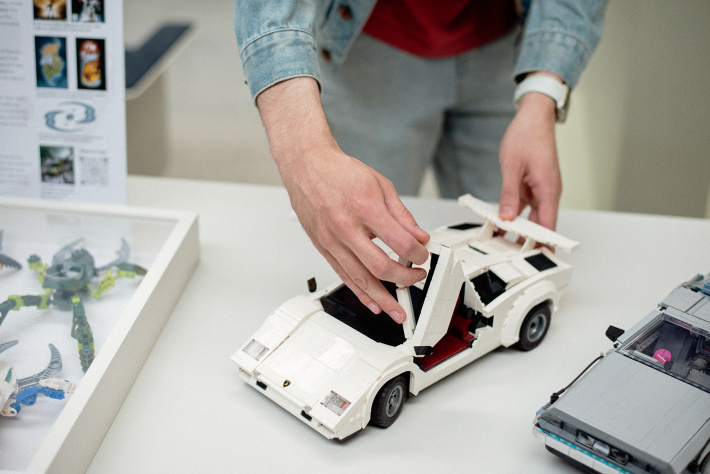

When Dylan Smith applied for his product-design degree course at Coventry University, he explained his desire to begin a career working with Lego. Likewise, when he applied for a student placement role at Vitsœ he outlined his dedication to working with Lego. Naturally, we at Vitsœ took note, resulting in a temporary exhibition of some of his collection alongside the Strong collection of Braun paraphernalia at Vitsœ’s production building.

Growing up in the vicinity of Royal Leamington Spa, Dylan watched the Vitsœ building being constructed. Researching the company further, he realised that we make the furniture designed by Dieter Rams, who he had learned about during his university studies. It therefore felt like a natural segue to apply for a student work-placement following completion of his degree course.

At Vitsœ’s biannual company meeting – where our global team come together (physically and remotely) – Dylan introduced himself by confidently charming us with Lego facts and theories.

Fact: It is theorised that Lego minifigs (an abbreviated term for minifigures) have outpopulated the number of humans on earth.

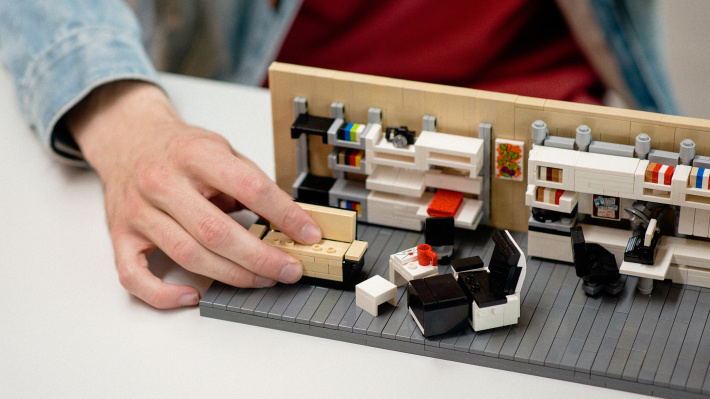

As an adult, viewing a display of Lego can be quite an emotional experience. It reignites memories of one’s own childhood – the emotional power of a beloved brand. Dylan has played this card well, by hitting a sweet spot with his colleagues in presenting – as one of the exhibits – a Vitsœ Lego diorama (title image). He explains “That was an idea I had pretty much since I started working here. I was interested to see how I could build that to scale. How could I translate the furniture using Lego? I created it on my computer software that I used to design my Lego work. When I brought it in [to Vitsœ] everyone was really positive, people enjoyed looking at it. I really wanted to make it look lived in. I've got some books on the shelves. I stuck a little camera on the top. I've also tried to make it look quite timeless as well. I didn't want to use any kind of modern technology in it, because I felt if I use a Lego computer, it wouldn't age very well. I went with a typewriter, that was kind of the alternative, because people still use typewriters.”

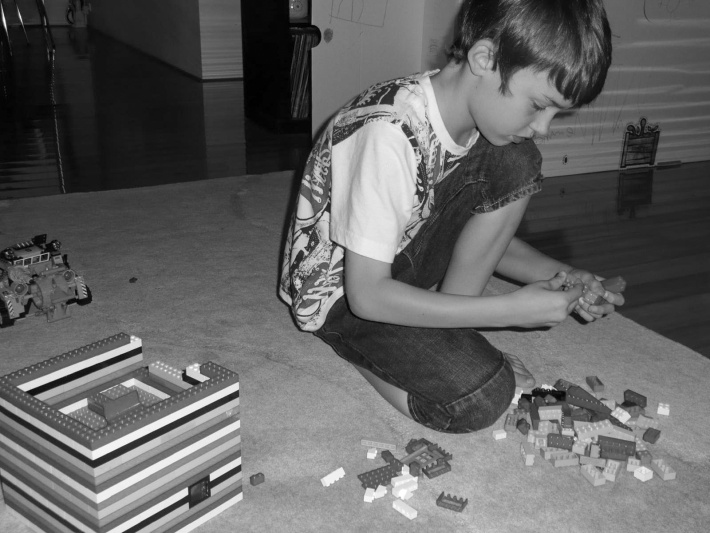

For Dylan an early inspirational Lego memory was watching an episode of the BBC TV Toy Stories series (2009), where presenter James May initiated the building of a full-scale Lego house which he lived in for 24 hours. Aged eight, Dylan set about building his own scale model. He was hooked. “For me, I think there's just something about the Lego system that cultivates my interest. I really like the problem-solving approach to it. I think that was one of the things I found interesting when I was doing my design work at university, this sort of trial-and-error approach, and coming up with different iterations and prototypes and models. Slowly progressing towards the finished product.”

His first two years of university studies were under the constraints of lockdown, which Dylan describes as “not very fun at all. Because we were in lockdown, we didn't have access to the buildings and all the resources of things that we usually get from university. It's interesting because a lot of people said they got into Lego during lockdown, but for me, I had a bit of what the Lego community call a ‘Dark Age’, which is where they're not really as involved with Lego.”

Working from home, Dylan found that he had to be quite rigorous at concentrating on his studies, and not get distracted. “I felt like I was pushing myself away from my hobbies and from Lego.” By his third year, the university campus had reopened, and things were running more smoothly. Not long after graduating Dylan started working at the Legoland shop in Birmingham. He explains this new employment “jump-started me getting back into doing my Lego projects; I rediscovered my passion for it.”

Dylan’s role while working at Vitsœ has played to his strengths. “I've been really enjoying building the desk shelves”. He’s also enjoyed the complexity of assembling the customer structural components (E-tracks, X- & H-posts) into the minimum-size packages for safely dispatching around the globe. “You've got to be quite strategic working out how you can fit the greatest number of components into the smallest size achievable. So, there is a bit of learning in working out the best solution to those sorts of problems”. And these are the details that customers notice and share feedback on, every day.

For Dylan it’s the challenge of replicating something from real life in Lego which challenges and progresses his creativity, as in the building of the Vitsœ diorama. “In order to get better at working with Lego, you have to learn to build real-life things that already exist, because it challenges your mind a little. To look at things that aren't made of Lego and try to visualise them; to work out how they go together with Lego and see where the Lego pieces could be used in that context.”

His exhibition at Vitsœ comprises less than 10% of his current total collection, which is now outgrowing his home. He cites the Bionicle pieces as resonating with a number of colleagues. “It was what kept Lego in business during the noughties. A lot of people my age look at that and they get really excited to see it. Yeah, it kind of triggers a feeling in them. A bit… what’s the word? Reminiscing.”

For others it’s his more recent reconstruction of his scale model of the James May house that strikes a chord. Dylan explains “Well, it's based on what was a real building. I looked at all the images and material that they took when they built the structure and then similarly to other projects where I build something that already exists, I look at it and go, ‘how can I shrink that down’. I'm looking at the shapes as a sea and working out what pieces I can use to create those shapes. And that was very much the case with the interior. I think the armchair was probably a good example, because that was a really complex shape to replicate with Lego. I had to work out how to create those soft curves – nothing is square. And because I was working with such a small size, that was intended to work with the Lego minifigure, I had to think outside the box.“

“One of the things they did say on my university course is you can spend literally forever designing and designing something and there has to be a point where you've got to say that you have to stop and accept that’s the furthest point you can go. That's also a case with Lego as well. But I think with Lego, because there's a finite number of different ways you can do something, it's a little bit easier to say, okay, that's it.” However, for Dylan and others those Lego parameters are rather broad as he has told us…

Fact: There are 915,103,765 different ways that you can attach six classic 2x4 Lego bricks together.